Patna: In the cracked, sun-scorched hamlets of Bihar’s Gangetic plains, where monsoon floods swallow entire seasons of hope and the earth bakes hard enough to blister bare feet, the Musahar community has survived for centuries on the thinnest edge of existence.

Their very name means rat-eaters, and it carries the weight of a stigma older than the republic. For generations, they survived by feeding on field rats from burrows with smoldering straw, roasted the meager catch over cow-dung fires, and divided the meal among children whose bellies bloated from chronic hunger.

This was never tradition. It was desperation. Over 96 percent of them own no land. Ninety-two percent labor on others’ fields for wages that disappear before the next sunrise. The 2011 Census recorded their literacy at 9.8 percent, which is lower than any Dalit group in India, with female literacy scraping 1 percent. In some villages, 85 percent of children showed signs of severe malnutrition. Malaria, kala-azar, and tuberculosis stalked households the state barely registered. Yet in one quiet corner of Patna, a retired policeman’s defiance has begun to rewrite this inheritance of despair.

Jyoti Kumar Sinha, a Padma Shri–honored IPS officer, never forgot the Musahar boy he saw naked and shivering on a winter night in 1980s Patna. In 2005, the year he retired, Sinha sold his Delhi flat, returned to Bihar, and founded Shoshit Seva Sangh. His new battlefield: a school.

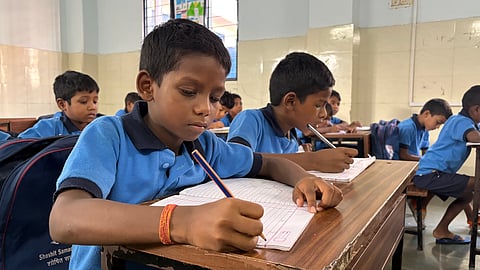

Shoshit Samadhan Kendra (SSK) opened with four boys. Today, 550 Musahar children, first-generation learners from all 38 districts of Bihar, study and live under one roof, entirely free. Uniforms, textbooks, medical care, three meals a day, even soap and toothbrushes: every paisa comes from donors who believe one educated child can torch an entire tola’s darkness.

Step through the iron gates on Shivalaya Road, and the transformation slams like a cool wind. Boys in school uniforms sprint across separate playgrounds, one for hockey, another for volleyball, coached by four full-time sports teachers. In the robotics lab, a Class 8 student solders circuits while explaining neural networks in fluent English. “We run AI and robotics workshops now,” says Principal Sushma Pandey, 44, who abandoned a cushy private-school job to mother these children. “Teaching them is different. It gives us inner satisfaction. I treat them like my own children.”

She distributes special concept notes, knowing many arrive unable to grip a pencil. Within a year, they grow and learn so much they could never have if this school wasn’t there. The numbers are only half the story. Since 2018, SSK passouts have scattered like seeds in rich soil. One student went on to become the first Musahar to earn an LLB. He now argues cases in Patna High Court. Another student, who was the son of a Phulwari Sharif brick-kiln worker, won the Dyer Fellowship to study in the US. Two students, childhood friends from Gopalganj, secured scholarships at Ashoka University. One alumnus serves in the Bihar bureaucracy; another teaches at a Delhi NGO.

They return during vacations, speaking of the change in their living standards and their “inclusion in the mainstream” and their “acceptance” in the society. Village elders who once feared that the school staff could be people involved in kidney-harvesting rumors and believed in rumpus, now queue at admission camps, begging for an LKG seat in this school. For all they know, if one child of theirs gets to study here, he will uplift their family for generations to come.

Rajeev Kumar, Chief Project Administrator, has witnessed this miracle for 18 years. “People used to ignore them or feel uneasy even talking to Musahars,” he says. “But here, they speak English, wear clean clothes, eat nutritious food, and live in a good environment. When they go home, they initiate change in terms of teaching their siblings, insisting on hygiene, and refusing early marriage.”

Inaugurated in 2007 by then-Governor R.S. Gavai and Lt Gen S.K. Sinha, the school started with four students. APJ Abdul Kalam once walked these corridors, blessing the library where Musahar boys now study. Teachers live on campus, and hostels pulse like joint families.

Seventeen-year-old Ayush Kumar Rawat from Gopalganj has lived here for a decade. His parents till others’ fields. No one in his family had ever entered a classroom. “I want to become a history professor,” he declares, eyes alight. “I read about Ashoka the Great and think maybe one day a Musahar will write the next chapter.”

Nearby, Deepak Kumar Rawat dreams of the civil services, while 18-year-old Vivek Kumar from West Champaran aims for engineering. “When I go home,” Vivek says, “my friends crowd around, wishing they’d passed the entrance test. They feel proud but regret their own chances.”

That regret is the spark. Alumni fund siblings’ fees, coach neighbors for SSK’s rigorous LKG exam, which is the only entry point—no lateral admissions allowed.

Beyond campus, ripples spread. In Musahar tolas, girls who once fetched water at dawn now attend government schools because elder brothers insist. The school also plans to widen its campus and open a new school exclusively meant for Musahar girls. “The plan is already in action,” says Rajeev Kumar. Liquor still flows, prohibition be damned, but educated sons drag fathers to de-addiction camps.

Jitan Ram Manjhi, the community’s tallest leader and former Chief Minister, often cites that Musahars can govern courtrooms and boardrooms. His Hindustani Awam Morcha fields Musahar candidates; voters who once sold votes for a bottle now demand manifestos.

The 2023 Bihar caste survey pegged Musahar literacy at 35 percent, which is seen as progress but glacial. Over 40 lakh strong, they remain vote banks more than power brokers. Child labor lures boys to brick kilns in states outside Bihar. Rats are still eaten in lean months, not from tradition but because mid-day meal kitchens close during floods.

In the hostels, boys polish shoes for the next day’s assembly. Outside the gates, Patna’s traffic roars past, oblivious. Inside, a community once cursed to crawl is learning to fly. One uniform, one certificate, one dream at a time, the rat-eaters are becoming the history-makers. And Bihar, for the first time in centuries, is listening.

-The authors Sumit and Shoaib are freelance journalists based in Delhi.

You can also join our WhatsApp group to get premium and selected news of The Mooknayak on WhatsApp. Click here to join the WhatsApp group.