Gujarat – The brutal murder of 20-year-old Dalit youth Nilesh Rathore in Jarikhiya village, Lathi taluka, Amreli district, on May 22, 2025, has brought back memories of a horrifying incident from 1936 in Borsad, Kheda district, Gujarat. Documented by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar in Writings and Speeches, Chapter 5: Unfit for Association, the 1936 incident reveals the deep-rooted caste discrimination faced by Dalits, a reality that tragically persists today, as seen in Nilesh’s death.

On March 6, 1938, at a meeting of the Bhangi community in Kasarwadi (behind Woollen Mills), Dadar, Bombay, chaired by Indulal Yadnik, Parmar Kalidas Shivram shared his harrowing experience. Kalidas, who had passed the Vernacular Final Examination in 1933 and studied English up to the 4th standard, initially applied for a teaching position with the Bombay Municipality but was rejected due to a lack of vacancies. He then applied for the role of a Talati (village patwari) through the Backward Classes Officer in Ahmedabad and succeeded. On February 19, 1936, he was appointed as a Talati in the Mamlatdar’s office in Borsad taluka, Kheda district.

Though his family hailed from Gujarat, this was Kalidas’s first visit to the region. Unaware that untouchability extended even to government offices, he mentioned his Harijan (Dalit) identity in his application, expecting his colleagues to be aware of his background. However, upon arriving at the Mamlatdar’s office, the clerk scornfully asked, “Who are you?” When Kalidas replied, “Sir, I am a Harijan,” the clerk retorted, “Go away, stand at a distance. How dare you stand so near me? If this weren’t an office, I would have given you six kicks—what audacity to come here for service!” The clerk then ordered Kalidas to drop his appointment letter and certificates on the ground before picking them up himself, refusing to take them directly.

Kalidas faced immense challenges in Borsad. At the Mamlatdar’s office, drinking water was kept in cans in the verandah, managed by a waterman who served other clerks. However, Kalidas was barred from touching the cans, as his touch was deemed polluting. He was given a small, rusty pot for his use, which no one else would touch or clean. The waterman, reluctant to serve him, often slipped away when Kalidas approached, leaving him without water for days at a time.

Finding a place to live was equally difficult. No caste Hindu in Borsad would rent him a house, and even the local Untouchables refused to offer lodging, fearing backlash from Hindus who disapproved of Kalidas’s attempt to work as a clerk—a position they believed was above his station. Food was another struggle; with no one willing to provide meals, Kalidas bought bhajias morning and evening, eating them in isolation outside the village. At night, he slept on the pavement of the Mamlatdar’s office verandah. After four unbearable days, he moved to his ancestral village, Jentral, six miles from Borsad, requiring him to walk eleven miles daily for a month and a half.

The Mamlatdar later sent Kalidas to train under another Talati responsible for Jentral, Khapur, and Saijpur villages, with Jentral as the headquarters. For two months in Jentral, Kalidas learned nothing and was barred from entering the village office. The headman of Jentral was particularly hostile, once threatening him: “You fellow, your father, your brother are sweepers who sweep the village office, and you want to sit in the office as our equal? Take care, better give up this job.”

The situation reached a breaking point when Kalidas was sent to Saijpur to prepare the village’s population table. Arriving at the village office, he found the headman and Talati working inside. Standing at the door, Kalidas greeted them with a “good morning,” but they ignored him. After standing outside for about 15 minutes, exhausted and humiliated, Kalidas sat on a chair nearby. Seeing this, the headman and Talati quietly left without a word.

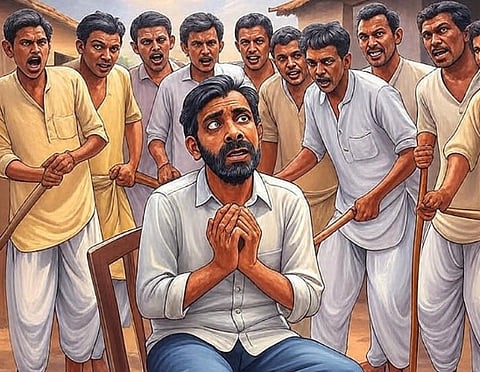

Within moments, a large crowd gathered around Kalidas, led by the village library’s librarian—an educated man whose involvement shocked Kalidas. It later emerged that the chair belonged to the librarian. Enraged, the librarian shouted at the Ravania (village servant), “Who allowed this dirty dog of a Bhangi to sit on the chair?” The Ravania forcibly removed Kalidas from the chair and took it away. Kalidas sat on the ground as the crowd stormed into the office, surrounding him. The mob, furious, hurled abuses and threatened to cut him to pieces with a dharya (a sharp, sword-like weapon). Kalidas pleaded for mercy, but the crowd remained unmoved.

Desperate to save himself, Kalidas had a sudden idea: he asked the Ravania for a piece of paper and, using his fountain pen, wrote a note to the Mamlatdar in bold letters: “To The Mamlatdar, Taluk Borsad. Sir, Be pleased to accept the humble salutations of Parmar Kalidas Shivram. This is to humbly inform you that the hand of death is falling upon me today. It would not have been so if I had listened to the words of my parents. Be so good as to inform my parents of my death.” The librarian read the note and immediately ordered Kalidas to tear it up, which he did. The crowd continued to insult him, saying, “You want us to address you as our Talati? You are a Bhangi and want to sit on the chair?” Kalidas begged for forgiveness, promising not to repeat the act and to resign from his job. The mob held him there until 7 PM before dispersing, with neither the Talati nor the headman returning during that time.

Deeply traumatized, Kalidas took 15 days’ leave and returned to his parents in Bombay. His story, shared at the 1938 Kasarwadi meeting, exposes the brutal reality of untouchability and caste violence in 1930s India. Kalidas’s quick thinking—writing the note to the Mamlatdar—likely saved his life by making the mob fear repercussions.

This 1936 incident bears a striking resemblance to the recent tragedy in Amreli. Nilesh Rathod and his three Dalit friends were attacked for addressing a shopkeeper’s son as “beta” while offering to help him reach a snack packet. The shopkeeper, offended by the term, assaulted them with an axe and called 10-15 accomplices who chased and beat the youths, leading to Nilesh’s death. Both incidents highlight the persistent caste-based discrimination that punishes Dalits for asserting basic dignity.

You can also join our WhatsApp group to get premium and selected news of The Mooknayak on WhatsApp. Click here to join the WhatsApp group.