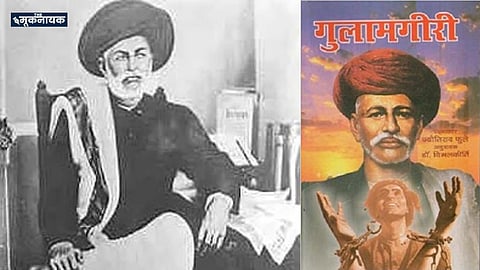

Originally written in Marathi, Gulamgiri (Slavery) is notable for its unique narrative style, where Phule engages in a philosophical and critical dialogue with a fictional character named Dhondirao. Through this imaginative correspondence, Phule addresses sensitive and often unspoken questions about the caste system, superstition, and religious orthodoxy — with striking clarity and courage.

Throughout the book, Dhondirao poses tough questions about Brahminism, the caste hierarchy, access to education, and the religious justifications for inequality. Mahatma Phule responds with bold, rational arguments that many even today would hesitate to express openly. The conversations are not just thought-provoking but also deeply engaging, making it difficult for readers to put the book down before finishing.

In the Hindi translation of the book, Phule's commentary on superficial religiosity, chanting rituals, the four Vedas, mystical trickery, restrictions on Shudras' education, and especially his critiques of the Bhagavata Purana and Manusmriti, stand out and grab the reader’s attention.

In Chapter 9, Mahatma Phule theorizes that the ancestors of Brahmins likely settled first in Bengal after arriving in India. From there, their practices of so-called mystical knowledge and magic likely spread. That’s perhaps why such practices were referred to as Bengali Vidya (Bengali magic). Phule suggests that like many uneducated people, these early Aryans believed in supernatural powers and engaged in public displays of “divine” tricks — the performers of which came to be known as Brahmins.

These Brahmin priests, Phule claims, consumed an intoxicating drink called Soma, which led them to mutter incoherently. They claimed to be in direct communication with God, and this spectacle inspired awe and fear among the common people. Using this fear, they manipulated and exploited the masses.

Phule argues that their Vedic texts themselves testify to such acts. Even in modern times, he says, Brahmin priests rely on rituals, chants, and so-called magic to deceive poor, uneducated farmers and laborers — tying sacred threads and selling illusions. Meanwhile, these hardworking people, toiling in their fields from sunrise to sunset, can barely find time to question such exploitation. They are burdened not only with feeding their families but also with paying taxes to the government.

At one point, Dhondirao challenges the claim that the four Vedas were created by Brahma himself and are divine in origin. Phule counters:

This claim by the Brahmins is completely false. If what they say is true, then why do the Vedas — supposedly emerging from Brahma’s mouth — contain verses written by several later Brahmarishis and Devarishis? Clearly, the Vedas were not composed by a single author at a single point in time. This has been conclusively demonstrated by several European scholars.

When Dhondirao asks whether the Bhagavata Purana was written around the same time as the Vedas, Phule responds:

To this, Dhondirao remarks:

Phule continues by asserting that the Manusmriti was written even after the Bhagavata Purana, and offers logical reasoning to support this:

“For instance, in the Bhagavata, the sage Vashishtha takes an oath saying, ‘I did not commit murder.’ The Manusmriti, in Chapter 8, verse 110, references this exact oath while discussing legal principles. Similarly, in Chapter 10, verse 108, it talks about the sage Vishwamitra eating dog meat during a famine. These cross-references clearly indicate that the Manusmriti came after the Bhagavata.”

Phule concludes that the Manusmriti is full of inconsistencies, making it unreliable as a moral or legal text.

You can also join our WhatsApp group to get premium and selected news of The Mooknayak on WhatsApp. Click here to join the WhatsApp group.